|

Earlier this week, the Supreme Court struck down a 1992 federal law that effectively prohibited sports betting in the United States, save for a handful of state-specific exceptions. In a 6-3 decision, the court ruled that the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) violated the 10th Amendment, which limits the federal government from controlling state policy.

The decision paves the way for states to decide whether to offer legal sports betting. ESPN’s David Purdum reports that New Jersey, which brought the case, Mississippi, New York, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia could be among the first to do so. The Associated Press reports that as many as 14 states could act within the next two years, with another 18 states to follow. So what does the decision mean for you? For starters, it’s likely to bring much of the estimated $150 billion-dollar-a-year black market in sports gambling above board.[1] You’ll conceivably be able to place a bet on your phone, at a local sportsbook, or even in an arena. Casinos should see a boost. And fans will have more reason to engage, which supports broadcasters, franchises, and leagues. Most importantly, however, the Supreme Court’s decision on sports betting means that you will now be able to lose your money legally – which, either right away or over time, you are exceedingly likely to do.

At the start of last NFL season, I walked through some of the success rates and financial dynamics of the most popular sports wager in the United States – the spread bet. I specifically looked at the against-the-spread performance of 60 individuals and 60 prediction models during the 2016 NFL season. I’ve since updated those statistics to include the 2017 NFL season.

To the unfamiliar, here’s an example of how a spread bet works. Assume the Dallas Cowboys are 4.5-point favorites at home against the New York Giants. If you pick Dallas to win “against the spread,” they need to win by five points or more for you to win the bet (“Dallas -4.5”). If you pick New York, you win if the Giants win the game outright or lose by four points or less (“Giants +4.5”). In a typical spread bet, you risk 10% more money than you would win (-110), known as a 10% “vig.” Bet $110 and win, and you get $100. Bet $110 and lose, and you lose all $110. Historically, sportsbooks would set and adjust point spreads to attract and maintain equal action on both teams.[2] Doing so guarantees the books a profit on those bets, equal to 4.5% of the total amount wagered.

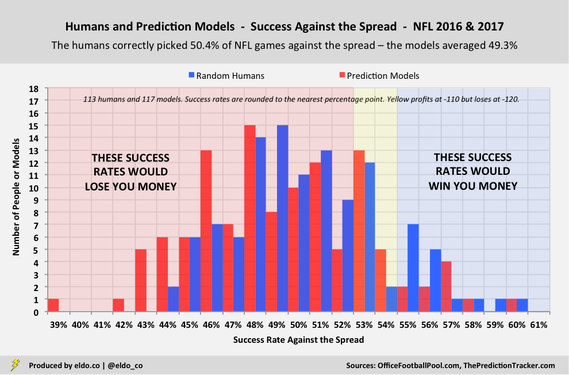

The chart below shows the results of a random group of individual bettors (60 in 2016 and 53 in 2017) and prediction models (60 in 2016 and 57 in 2017) “against the spread” over the course of the last two NFL regular seasons. As expected, both groups had an average success rate right around 50%. And while the sample size is still small, you can see a typical bell curve forming.

Half of the bettors won more games than they lost, and half lost more games than they won. But when losses cost $110 and wins only earn $100 – thanks to that 10% vig – things get pretty ugly pretty fast. Had everyone wagered real money on every game in equal amounts, only 30 out of 113 individuals (27%) would have netted a single-season profit. Nearly three-quarters of bettors would have lost money.[3]

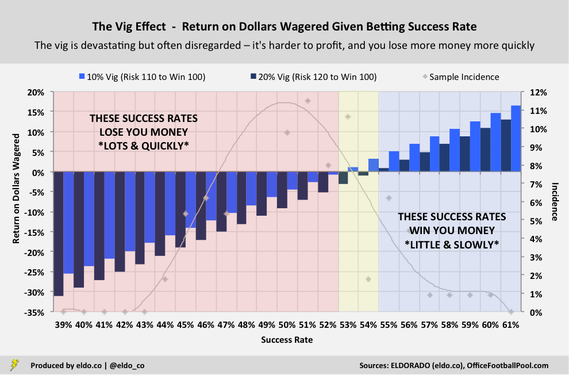

Now consider this. Certain professional sports leagues have been lobbying to receive an “integrity fee” for all wagers placed on their respective games, theoretically compensating them for “[creating] the source of the activity” and “[bearing] the majority of the integrity risk.” Fee estimates range from 0.25% to 1.0% of money wagered, or 2.5% of profits, with other wrinkles attached. Sports betting operators will also have to pay taxes – potentially as high as 12.5% of gross sports wagering revenue in one version of an Illinois bill. Against this backdrop, rumors began to circulate last fall that sportsbooks might consider covering these taxes and fees by raising the standard vig from 10% (-110, risk $110 to win $100) to 20% (-120, risk $120 to win $100). If that happens, your chances of making money get even dimmer. With a 10% vig in the example above, we saw how roughly three out of four individual bettors would have lost money – already pretty tough sledding. With a 20% vig in the same example, nearly seven out of eight would have lost money on a single-season basis – worse still, 95% of the individuals who were part of the sample in both years would have lost money over the course of the two seasons combined.[4]

Let's take a closer look at just how devastating the vig is. With a 10% vig, only three out of 113 individuals (2.7%) would have netted a single-season return-on-dollars-wagered of 10% or more. Meanwhile, 22 people (19.5%) would have had a 10%+ loss. Only 18 of the individuals would have earned a 3%+ profit, while 61 bettors would have lost at least that much. And the 20 worst performers would have lost over 2.0x the money that the 20 best performers gained.

Now let’s repeat those sentences assuming a 20% vig. With a 20% vig, only one out of 113 individuals (0.9%) would have netted a single-season return-on-dollars-wagered of 10% of more. Meanwhile, 50 people!!! (44.2%) would have had a 10%+ loss. Only four of the individuals would have earned a 3%+ profit, while 83 bettors would have lost at least that much. And the 20 worst performers would have lost almost 8.0x the money that the 20 best performers gained. And again, those are single-season returns. It's even harder to stay in the black year over year. With a 10% vig, bettors in this example would have had to finish in the 90th percentile in 2017 just to offset the damage of finishing in 50th percentile (i.e., being exactly average) the year before. (Remember that half of the bettors did even worse!) With a 20% vig, they'd have had to finish in the 97th percentile in 2017 to recoup the money they lost by finishing in the 65th percentile (above average!) the year before. In other words, the reward for being good-but-not-great is a financial penalty and a requirement that you be exceptional next year to break even. You can deduce from the chart how ugly it gets when you're actually below average, like half of everybody is.

Despite all that, most folks kinda pretend the vig isn’t there, casually chalking it up as the cost of doing business. Ask your buddy how much he has on a game, and he’ll likely say “$100” or $50,” not “$110” or “$55,” which is really what he’d lose. If he wins two bets and loses two others, he’ll probably tell you that he went two and two, not that he lost money.

Of course, not everyone puts money on every game. Bettors often target select games. But even then, one person's "best bet" is another's "trap of the week," and over a long enough period, the vast majority of casual bettors will lose money. There’s nothing special about the math. Sometimes we just need to see it all on paper.

Footnotes

[1] Market estimates vary wildly, from $67 billion to $380 billion. For context, Nevada sportsbooks handled $4.8 billion in sports wagers in 2017. [2] Evidence suggests that sportsbooks have grown increasingly comfortable straying from that 50-50, guaranteed-profit balance. When they do so – that is, when they set lines that attract significantly more money on one team – they’re effectively betting on the other team. In early 2017, certain books allowed big imbalances in nine of 10 NFL playoff games. The books lost all of them against the spread. [3] In this particular sample, that's true both on a single-season basis and combined over the course of the two seasons. There were 60 individuals in 2016 and 53 individuals in 2017. Forty-two of them were the same across seasons. On a single-season basis, 83 out of 113 (73%) would have lost money with a 10% vig. On a combined basis over the two seasons, 31 out of 42 (74%) would have lost money with a 10% vig. [4] Again, there were 60 individuals in 2016 and 53 individuals in 2017. Forty-two of them were the same across seasons. On a single-season basis, 97 out of 113 (86%) would have lost money with a 20% vig. On a combined basis over the two seasons, 40 out of 42 (95%) would have lost money with a 20% vig. Portions of this story were updated and adapted from one of my previous posts.

Data was compiled and analyzed by ELDORADO. All charts and graphics herein were created by ELDORADO.

437 Comments

6/30/2020 06:22:52 am

You just shared all the information very nicely here. Keep sharing.

Reply

4/20/2021 02:53:25 am

Great article! I also made a lot of money on sports betting recently

Reply

5/31/2021 10:40:18 am

Nice your blog regarding gaming and how to play games. This is the best blog I have ever read. It’s really a helpful post. Gain some experiences reading this post. <a href=" https://www.5g999.co/slot/spadegaming/. Appreciate your hard work regarding this wonderful article glad to read this post keep on update us. Thanks for sharing this amazing blog.

Reply

6/13/2021 11:38:58 pm

Great Post! You are sharing a wonderful post. Thanks and keep sharing.

Reply

7/28/2021 04:25:54 am

thanks for your time, Great Article, the bettings is cool only when the sites providing can be trusted! i had enough trouble before but now i found <a href="https://sportstoto.games/" title="안전놀이터">안전놀이터</a>

Reply

10/20/2021 03:57:38 am

I seriously liked, I want details about it, since it is rather wonderful., Cheers pertaining to expressing.

Reply

10/26/2021 04:10:07 am

<a href="https://gamerszonegaming.com/"> Best online sports betting site </a>. Get a betting id in 5mins. Grab the offer on the first deposit.

Reply

11/12/2021 12:11:48 am

Nice write-up indeed. Thanks for providing this blog.

Reply

11/16/2021 01:18:24 am

Awesome write-up indeed. Looking forward to more ideas.

Reply

11/17/2021 12:25:32 am

Hello everyone, I have a nice new website here. This is the best online casino in Asia called THA(https://thienhabet.pro/). Welcome everyone to play

Reply

1/12/2022 11:17:21 pm

What a fantastic piece of writing. There is a lot of useful information here. Thank you for providing this information.

Reply

บทความของ MEGA GAMEในวันนี้ <a href="https://www.mega-game.io/pgสล็อต/"> PG SLOT</a> ยืนหนึ่งในเกม สล็อต ที่ได้รับความชื่นชอบ และเป็นที่พูดถึงอย่างมาก ในเวลานี้เลยก็ว่าได้ นักเสี่ยงโชคหลายคน อาจจะงงว่า จุดเริ่มต้นในเกมนี้ มันเกิดขึ้นมาได้อย่างไร ด้วยเหตุผลอะไร ที่ทำให้เกมสล็อต ได้รับความนิยม และการเล่นเกม <a href="https://betflixauto89.com/betflix/">betflix</a> มันเล่นยากมากน้อยแค่ไหน มีสิ่งไหนที่จะต้อง ระวังบ้าง ถ้านักเสี่ยงโชคหลายท่าน สงสัยเรื่องนี้ บทความของเรา วันนี้มี ความนิยม ของเกม PG สุดยอดค่ายเกมอันดับ1<a href="https://betflik.to/betflik/">betflik</a> มาให้ท่านได้ศึกษา พร้อมแล้วไปดู ความนิยมของเกมนี้ ในกลุ่ม นักเสี่ยงโชคกันเลย

Reply

<a href="https://www.megagame168.co/%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%99%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95-mega-game/"> MEGA GAME </a>ทางเว็บของเรามีเคล็ดลับหารายได้จากการเล่นสล็อตทุกค่ายมาแนะนำให้ท่านได้เรียนรู้ และสนุกไปด้วยกันอีกมากมาย ในตอนนี้การหารายได้ออนไลน์มีหลากหลายรูปแบบ เล่นสล็อต MEGA GAME ไม่ว่าจะมาจากวิธีขายผลิตภัณฑ์เสริมของเกม MEGA GAME หรือไม่ PGSLOT ก็การขายของได้เงินจริง เกี่ยวกับบนสิ่งออนไลน์ แต่ว่าไม่ว่าจะอะไรก็แล้วแต่อย่างไรก็ตามบางครั้งก็อาจจะจำต้องใข้ทุนที่สูงมากมาย ๆ

Reply

สวัสดีนักเสี่ยงโชคทุกท่านวันนี้ MEGA GAME ขอนำเสนอ แจกสูตรสล็อต <a href="https://www.mega-game.io/แจกสูตรสล็อต/"> PG SLOT</a> ฟรี ใช้ได้ จริง ใหม่ล่าสุด 2022 สูตรสล็อตคืออะไร ใช้ง่ายได้เงินจริงไหม <a href="https://betflixauto89.com/betflix/">betflix</a> นักเสี่ยงโชคหลายท่านอาจจะสงสัย สูตรสล็อต pgล่าสุด 2022 พัฒนามาจากโปรแกรม AI หรือเรียกอีกอย่างหนึ่งว่า ความอัจฉริยะ โปรแกรมที่สามารถ คิดวิเคราะห์เชิงลึก และประมวลผล ในฐานข้อมูลขนาดกว้างได้อย่างตรงปก โปรแกรมสแกนสล็อต pg ฟรี 2022 สูตรเล่นเกมสล็อต pg แตกง่าย ว่าด้วยเรื่องของเทคนิคหลาย ๆ ด้านได้นำโปรแกรม อัจฉริยะ มาประยุกต์ใช้ รวมทั้ง <a href="https://betflik.to/MEGAGAME/">MEGAGAME</a> โปรแกรมสูตรสล็อต ฟรี PG สูตรสล็อต ใช้ได้ จริง ด้วยความมีคุณภาพของโปรแกรม โปรแกรมสูตรสล๊อตฟรี

Reply

<a href="https://www.mega-game.io/%e0%b8%96%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%99%e0%b9%84%e0%b8%a1%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%b1%e0%b9%89%e0%b8%99/"> MEGA GAME </a> เมก้าเกม ถอนไม่อั้น จ่ายจริงแน่นอน 100% ที่เว็บ MEGA GAME เล่นเกมสล็อต ได้ไม่มีจำกัด ยิ่งเดิมพัน ยิ่งมีลุ้น เริ่มต้นลงทุนแค่ 1 บาทก็ลุ้นได้ มีเกมให้เลือก มากกว่า 1,000 เกม แตกง่าย โอกาสรับ รางวัลเยอะ สมัคร MEGA GAME รับสิทธิ พิเศษที่ ที่จะช่วยให้ คุณเดิมพัน ได้สะดวก มากยิ่งขึ้น

Reply

<a href="https://www.betflix-pg.com/blogs/enter-slot-game-pg/ ">BETFLIX</a> สล็อตออนไลน์ PG SLOT ที่สุดของเกมออนไลน์ เล่นเกมบนสมาร์ทโฟน แบบล้ำเลิศสุด เข้าเกมสล็อตPG สมัครเล่นสล็อตกับ BETFLIX วันนี้รับโบนัส แรกเข้า 100% ทันที โบนัส 50% สำหรับสมาชิกใหม่ ด้วยความพิเศษของ พีจี สล็อต ที่มีรูปแบบของการเล่นที่ง่าย รูปแบบเกมแบบใหม่ ไม่น่าเบื่อ ไม่จำเจ ในแบบการเล่นเดิมๆ อีกต่อไป เข้าเกมสล็อตPG เป็นเกมที่แจ๊คพอต mega game แตกบ่อยที่สุด ได้โบนัส อย่างรวดเร็ว แค่ 5 นาที ก็สามารถเปลี่ยนท่าน เป็นเศรษฐีคนใหม่พร้อมที่จะรวย ไปกับ pg slot เว็บตรง หรือยัง? ถ้าพร้อมแล้ว ปุ่มสมัครสมาชิกด้านล่าง สมัครเล่นได้เลย ตอนนี้ และรับโบนัส สมัครใหม่ ไปด้วยเลย สมาชิกเก่า ก็มีโปรโมชั่นทุกวัน รับได้ทุกวันเลย <a href="https://www.megagame168.co/">mega game</a>

Reply

<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%a2%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%99%e0%b8%b4%e0%b8%a2%e0%b8%a1-%e0%b9%81%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%87%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%a2/">betflix</a>

Reply

<a href="https://www.mega-game.io/%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%a7%e0%b8%a1%e0%b9%82%e0%b8%9b%e0%b8%a3%e0%b9%82%e0%b8%a1%e0%b8%8a%e0%b8%b1%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%99%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%b8%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%b8%e0%b9%89%e0%b8%a1/"> MEGA GAME </a>พิเศษ รวมโปรโมชั่นสุดคุ้ม กับ เมก้าเกม 2022 หนึ่งในโปรโมชั่นยอดฮิต จากเมก้าเกมที่เรา แนะนำให้ เข้ามาสัมผัสด้วยตัวเอง เดิมพันไม่ต้องกังวล เรื่องเล่นแล้วเสีย เพราะยิ่งเสีย ยิ่งได้ ไม่เพียงแค่โปรโมชั่นนี้เท่านั้น ที่คุณจะสามารถรับได้ กับ MEGA GAME เพราะเรายังมีโปรโมชั่นเด็ดๆ อีกมากมาย รับได้ทั้งวัน ไม่มีกั๊ก

Reply

<a href="https://www.mega-game.io/pg-slot-%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%b5%e0%b9%86/"> MEGA GAME </a>ค่าย PG Slot เว็บดีๆ คือเว็บสล็อตที่ได้รับความ นิยม อย่างมาก มีเกมสล็อต MEGA GAME ให้เลือก เล่นมากกว่า 100 เกม แล้วยังมีเกมอื่นๆ ให้เล่น อีกมากมาย ปัจจุบันสามารถเข้าเล่น ได้กับทุก แพลตฟอร์ม จะเล่นผ่าน คอมพิวเตอร์ แท็บเล็ต หรือ โทรศัพท์ มือถือก็ได้เช่นกัน

Reply

<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%a3%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b5%e0%b8%a2%e0%b8%99%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b9%e0%b9%89%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%a1%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%b4%e0%b9%82%e0%b8%99/">betflix</a>

Reply

<a href="https://www.megagame168.co/%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%a7%e0%b8%a1%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%a1%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95/"> MEGA GAME </a>เเหล่งรวบรวมเกมคาสิโนออนไลน์ MEGA GAME เว็บที่รวมเกมสล็อตทุกค่ายที่ขึ้นชื่อมาใว้ให้ท่านแล้ว ในเว็บเดียว ทางเว็บของเราได้รวมไว้ให้ม่านแล้ววันนี้ อาทิ เช่น เกมคาสิโนชื่อดัง เกมไพ่ เกมสล็อต และเกมอื่นๆ อีกมากมาย มีเกมให้ท่านเลือกเล่นมากกว่า 1,000 เกม เว็บรวมเกมสล็อต ค่ายสล็อตน้องใหม่มาเเรง สมัครสมาชิกได้ง่ายๆแล้ว เพียงท่านสมัครวันนี้ แล้ท่านจะได้รับฟรีๆ รับทันทีเครดิต 100 จากทางเว็บเราเว็บเดียว ด้วยระบบออโต้ สามารถ ฝาก – ถอนเงินได้ตลอด 24 ชั่วโมง พร้อมโปรโมชั่นพิเศษจัดให้ทุกคนเเบบจัดเต็มทุกระบบ

Reply

สวัสดีชาว MEGA GAME วันนี้เราจะมารีวิว<a href="https://www.mega-game.io/mega-game-ซื้อฟรีสปินสล็อต/"> MEGA GAME</a> ซื้อฟรีสปินสล็อต ปั่นง่ายระบบ Mega game สล็อต แตกง่ายขึ้นกว่าเดิม Mega game 789 เพิ่มโอกาส สล็อตแตกได้ง่ายกว่าเดิม MEGA GAME โดยไม่ต้องเล่นแบบ หนักหน่วง และไม่ต้อง ลงทุนหนัก MEGA GAME 777 แต่เพิ่มโอกาส พีจีสล็อต แตกง่าย MEGA GAME SLOT ให้นักเสี่ยงโชคผู้เล่น แบบใส ๆ<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/betflix/">betflix</a> เล่นเยอะเพิ่มโอกาส ทำเงินเยอะ Mega game 1688 ทั้งโบนัส แจ็กพอตแตกง่าย Mega game สล็อต ไม่ต้องเสียเวลารอรอบ Mega game 789 จังหวะแทงสวน ทำแจ็กพอตแตก MEGA GAME เพียงอย่างเดียว นักเสี่ยงโชคก็สามารถ ใช้ทริคทำ สล็อตซื้อฟรีสปิน ได้ไม่ยาก MEGA GAME 777 หากเล่นอย่างมีชั้นเชิง megagame auto บวกกับทักษะ การเดิมพันที่ดีด้วยแล้ว MEGA GAME SLOT การทำเงินกับการเล่น สล็อตออนไลน์ ของนักเสี่ยงโชคก็จะกลายเป็น เรื่องที่ง่ายสุดๆขึ้นมาทันที Mega game abx แนวทางทำเงินออนไลน์ กับเกมสุดมันส์ Mega game 1688 ที่เล่นกัน ทั่วบ้านทั่วเมือง Mega game สล็อต ซื้อฟรีสปิน ง่ายๆ รับโบนัส MEGA GAME ในการหมุนทันที ซึ่งฟีเจอร์ สŪ

Reply

<a

Reply

3/13/2022 05:18:02 am

<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95pg-%e0%b9%81%e0%b8%88%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%9f%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b5%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%b4%e0%b8%95/">betflix</a>สุดจัดปลัดบอก ต้องมาบอกต่อ สล็อตPG แจกฟรีเครดิต ฝากถอน ไม่มีขั้นต่ำ ที่ให้บริการ สล็อตฝากถอน ไม่มี ขั้นต่ำ ผู้เล่นทุกท่านสามารถร่วมสนุกกับ BETFLIX เลือกเล่นเกมสล็อต pg เครดิตฟรี 50 ไม่ต้องแชร์ล่าสุด ได้ง่าย ๆ ด้วยระบบก ฝากถอน ไม่มี ขั้น ต่ำ 2022 ที่ทำให้ผู้เล่นทุกท่าน นั้นทำรายการต่าง ๆ ได้ด้วยตัวผู้เล่นเอง และ สะดวกสบายมาก

Reply

<a href="https://www.betflix-pg.com/blogs/bet-on-online-slots-games/">BETFLIX</a> โดยปัจจุบันนี้ผู้เดิมพันก็คงเห็นกันอยู่แล้ว ว่าสล็อตออนไลน์ เป็นเกมที่คนให้ความสนใจกันเป็นอย่างมาก BETFLIX เป็นเว็บเกมออนไลน์ที่ไม่ผ่านคนกลาง เว็บส่งตรง ถึงมือให้ผู้เดิมพันได้ สนุกจุใจ แบบไร้กังวล เพราะ เดิมพันเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ ดีที่สุด แต่อีก 1 มุมผู้เดิมพันก็คงเห็นว่ามีเว็บไซต์หลายเว็บ ที่เปิดให้บริการเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ หรือเว็บเดิมพันหลายๆชนิด ผู้เดิมพันไม่ควรไว้ใจมากนัก ควรศึกษา ละ ทำความเข้าใจให้ดีก่อน ที่จะร่วมลงทุน แต่วันนี้เราขอเสนอ megagame เว็บ สล็อตได้เงินง่าย ที่ไม่ทำให้ท่านผิดหวังแน่นอน เพราะเรามี แฟนตัวยงเข้ามาร่วมสนุก มากกว่า 2,000 ต่อวันกันเลยทีเดียว <a href="https://www.megagame168.co/">mega game</a>

Reply

<a

Reply

<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%87%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a1%e0%b8%b1%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%9f%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b5/">betflix</a>ข้อเสนอดีๆ จากเว็บ BETFLIX สล็อตเว็บตรงสมัครฟรี ที่จะทำให้ ผู้เล่น ได้รับโอกาส ในการสมัครเล่นฟรี ไม่ต้องเสียค่าใช้จ่าย กับสล็อตเว็บตรงสมัครฟรี แถมยัง ได้ร่วมสนุก กับเกมสล็อต ได้ครบทุกค่ายชั้นนำ โดยการ ใช้เงินทุน เพียงเล็กน้อย แต่ลุ้นรับ เงินรางวัล กลับมา อย่างคุ้มค่า มากที่สุด สมัครเล่น แค่ครั้งเดียว สามารถเล่นเกมสล็อต ได้ทุกเกม ครบจบทุกการบริการ ในเว็บเดียว สล็อตเว็บตรง เครดิตฟรี โดยที่ ไม่จำเป็นต้อง ไปหาสมัครเล่น กับเว็บอื่น หลายเว็บ ให้ยุ่งยาก

Reply

<a href="https://www.megagame168.co/%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%99%e0%b8%87%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%a2%e0%b9%81%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%81%e0%b9%84%e0%b8%a7/"> MEGA GAME </a>เกมสล็อตออนไลน์ เป็นเกมที่ได้รับความนิยม เป็นอย่างมาก ซึ่งการลงทุนเล่น สล็อตเล่นง่ายแตกไว ทั้งสนุกสนาน เล่นง่ายเพลินมีความสุข สร้างราย ได้ให้กับผู้เล่นได้จริง ในสมัยนี้ผ้เล่นทุกคน สามารถเข้าถึงการลงทุนเล่นเกมสล็อตได้กันทุก ๆ คนไม่ว่าจะเป็นผู้เล่นคนไทย หรือชาวต่างชาติ เพียงแค่สมัครเว็บ ไซต์ ที่เปิดให้บริการไม่กี่ขั้นตอนผ้เล่นก็เริ่มต้นลงทุนกับเกม ตัวต่อรายได้ในทันที โดยการเข้าใช้บริการบนเว็บไซต์สามารถทำได้โดย ง่ายเล่นได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลา ไม่ว่าจะอยู่ที่ใดก็ร่วมสนุก ตื่นเต้นและคลายเครียดจากการเดิมพันเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ได้ตลอดสล็อต เล่นง่าย แตกไว MEGA GAME ที่สุดสล็อต แตกง่าย แตกบ่อย กลายเป็นสิ่งที่นักพนันทั้งหลายต่างก็ชื่นชอบ และ ถูกอกถูกใจกับเกมของทางเว็บของเราเพราะนอกจาก จะได้ เล่นเกมสล็อต เพื่อความสนุก สนานยังสามารถ&#

Reply

<a href="https://www.mega-game.io/%e0%b8%84%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%a2%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%a1%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%a3%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%b2/"> สล็อต </a>การเล่นเกมมีความสนุกสนานกับ MEGA GAME ค่ายเกมบาคาร่า จะกลายเป็นอีกหนึ่งช่อง ทางการเล่นเกม ที่หลากหลายขึ้นให้คุณ นั้นได้มีโอกาสที่ จะสร้างความ บันเทิงให้กับตัวคุณเองได้ อย่างแน่นอน เพราะทุกวันนี้การเดิมพัน เกมไพ่บาคาร่าออนไลน์ นั้นก็มีหลากหลาย ผู้ที่คอยสร้างเกมไพ่ มาให้คุณได้เข้าเล่น กันเป็นอย่างดี นั่นเอง และรวมไปถึงในเรื่อง

Reply

<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%99%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95%e0%b9%84%e0%b8%a1%e0%b9%88%e0%b9%82%e0%b8%ab%e0%b8%a5%e0%b8%94%e0%b9%81%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%9e/">betflix</a>วันนี้ BETFLIX จะมาแนะนำ เล่นสล็อตไม่โหลดแอพ เป็นผู้ให้บริการเกมทำเงิน ออนไลน์ผ่านมือถือ ที่มีเกมให้เลือกเล่นหลากหลายรูปแบบ มีเกมรูปแบบใหม่ ที่ทำเงินได้ง่าย ให้ผู้เล่นได้รับเงินเร็ว ได้ใช้เงินจริง เป็นเว็บสล็อตที่ไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์ สล็อตเว็บตรง ที่เล่นง่ายๆ ให้บริการเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ และเกมชั้นนำ อีกมากมาย ทุกเกมมีสิ่งที่น่าสนใจเป็นพิเศษ ไม่ว่าจะเป็นระบบกราฟิกของเกม ภาพประกอบ และดนตรี ที่ให้ความสนุกมากยิ่งขึ้น

Reply

4/5/2022 06:43:36 pm

Thank you for this very informative article! Keep on posting.

Reply

<a href="https://www.betflix-pg.com/pg/ganesha-fortune-betflix/">BETFLIX</a> หากใครกำลังมองหาสล็อตออนไลน์เว็บไซต์ BETFLIX เกมสล็อตน้องใหม่ไฟแรง จากค่าย PG SLOT สามารถลองเล่น ได้แล้ววันนี้ สนุกสนานสุดมันส์ เล่นเกมได้เงิน Ganesha Fortune เกมสล็อตออนไลน์ตลอด 24 ชั่วโมง ไม่มีหยุดพัก Pillar Fortune ทดลองเล่น เกมสล็อต megagameโชคลาภแห่งคเณศ ระพิฆเนศ เทวดาผู้เป็นใหญ่แห่งความสำเร็จ ที่ได้รับการยกย่องเทิดทูน จากชาวบ้าน มานานแสนนาน หลายๆ คนเชื่อกันว่า ด้วยความรู้รอบคอบ และ ความสง่างามของเขา จะทำให้ลูกศิษย์ มีความสุขความเจริญ และมีความมั่งคั่ง และประสบความสำเร็จในชีวิต ทดลองเล่นสล็อตฟรี อัพเดท2022 ได้แล้ววันนี้ <a href="https://www.megagame168.co/">megagame</a>

Reply

4/21/2022 05:33:17 am

<a href="https://www.jackergame.com/" target=_blank>Joker123</a>

Reply

<a href="https://megagame.io/%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%87-premium/"> MEGA GAME </a>อยากเล่นเกมสล็อตได้ทุกเกมไหม หากอยากเล่นสล็อตให้ ได้ทุกเกมต้องมาเล่นที่ สล็อตเว็บตรง Premium ที่จะให้คุณได้เล่นเกมสล็อตจากทุกค่ายเกมดังไม่ว่าจะเป็น PG Slot , Joker , Sexygaming , JDB , Ebet รวมทั้งค่ายเกมอื่นๆได้กว่าพันเกม ให้คุณเดิมพันได้อย่างไม่มีขั้นต่ำ ทางเลือกใหม่ในการเดิมพันที่มากกว่ากับ สล็อตเว็บตรง พรีเมี่ยม แถมยังฝากถอนได้อย่างไม่มีขั้นต่ำเช่นกัน MEGA GAME ผ่านระบบออโต้ ที่เว็บสล็อตเว็บอย่าง MEGA GAME หากคุณคือคนที่ชื่นชอบเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ใหม่ๆ

Reply

เกมเล่นผ่าน ระบบออโต้ และ ออนไลน์<a href="https://mega-game.io/mega-game-megagame-65/"> สล็อต</a>เล่นเกม ผ่านบน มือถือ MEGA GAME ได้ ไม่ต้อง ผ่านเอเจ้นท์ใด ๆ ทั้งนั้น เล่นง่าย ได้จริง เกมสล็อต ติดอันดับล่าสุด Megagame 65 เราได้รวม รวมเกมไว้มาก กว่า 50 ค่าย มีเกมให้ เลือกกว่า 5000 เกม เพียง ผู้เล่นแค่สมัคร เท่านั้นเองเล่นได้ ทุกเกมสะดวก สบายอีกด้วย ทางเราไม่มี โกงผู้เล่นใด ๆ ทั้งนั้น

Reply

4/24/2022 01:13:22 pm

Thanks for sharing such an Amazing information, I Couldn’t leave without reading your blog.

Reply

<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/the-most-popular-slots/"> BETFLIX </a>เนื่องจาก กระแสของเกมสล็อต ในปัจจุบัน ที่สามารถ สร้างรายได้ ให้กับผู้เล่น ได้เป็นจำนวนมาก ทำให้ผู้คน ต่างสนใจ และเข้ามา ทำเงินกัน อย่างล้นหลาม และต่างต้องการ ที่จะเข้าเล่นเกมกับ เว็บสล็อตมาแรง BETFLIX เว็บสล็อต ที่มีคนเล่นมากที่สุด เพราะเรา เป็นเว็บที่มีคุณภาพ มากที่สุด และสามารถ ไว้วางใจ ว่าปลอดภัย

Reply

<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%a7%e0%b8%a1%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95-%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%ad%e0%b9%82%e0%b8%95%e0%b9%89/">betflix</a>แหล่งรวมเว็บ สล็อต BETFLIX รวมสล็อต รวมเว็บสล็อตฝากถอน ไม่มี ขั้นต่ำ เว็บสล็อตทุกค่าย เว็บสล็อตออโต้ หากนักเล่นเกมสล็อตชอบเกมสล็อตและมีเกม รวมเว็บสล็อต ออโต้ เว็บสล็อตแตกง่าย 2022 ฝากถอน ไม่มี ขั้นต่ํา เกมโปรด หลายเกม รวมเว็บสล็อต<a href="https://impact-360.org/wild-west-gold/">wild-west-gold</a> 2021-2022 เว็บรวมสล็อตทุกค่าย และ เว็บสล็อตทุกค่าย หรืออยากที่จะเล่นเกมสล็อตหลายเกม โดยที่

Reply

5/5/2022 08:30:40 am

your website is very nice, the article is very enlightening, I wish you continued success.

Reply

<a href="https://mega-game.io/%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%b4%e0%b9%82%e0%b8%99%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%99%e0%b9%84%e0%b8%a5%e0%b8%99%e0%b9%8c%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%87/"> สล็อต </a>เว็บเกมเดิมพันออนไลน์ คาสิโนออนไลน์เว็บตรง ไม่ผ่านตัวแทน MEGA GAME ที่มีเกมให้ คุณได้เข้าใช้ บริการอย่าง ครบครัน มากกว่า 2200 เกม ซึ่งเว็บของเรา นั้นเป็น เว็บเกมระบบ Auto เมื่อคุณได้สมัคร เป็นสมาชิก กับเราคุณจะได้เจอ กับระบบเกม ที่มีความเสถียร ที่สุด อีกทั้งเกมต่างๆ ที่เรามีนั้นยัง เป็นเกมโบนัส ออกบ่อย ถ้าคุณได้เข้าเล่น ไม่ว่าจะเป็น

Reply

สวัสดีสมาชิก <a href="https://betflixauto89.com/เว็บตรงฝากถอน1บาท/">BETFLIX</a> ทุกท่าน วันนี้เราจะมาแนะนำ <a href="https://themonarchalliance.org/เว็บตรงฝากถอน1บาท/">เว็บตรงฝากถอน1บาท</a> จัดหนักจัดเต็ม กับการสร้างรายได้ในยุคสมัยใหม่ โดยไม่จำเป็นต้องลงทุนเยอะ เราเข้าใจหัวอกคนที่มีค่าใช้จ่ายเยอะ ต้องประหยัด อย่างนั้นเว็บไซต์ของเรา <a href="https://insurancedallas.info/เว็บตรงฝากถอน1บาท/">เว็บตรงฝากถอน1บาท</a> จึงไม่มีข้อจำกัดด้านวงเงิน สล็อต เบ ท 1 บาท ฝากถอน ไม่มี ขั้นต่ำ สามารถเล่นได้อย่างสนุกสนาน เพียงมีแค่ 1 บาท ท่านก็สามารถทำกำไรได้แล้ว ฝากถอนไม่มีขั้นต่ำ เล่นได้อย่างสนุกสนาน ทำกำไรได้อย่างสบายใจ ไม่ว่าท่านจะลงทุนเท่าไหร่ MEGA GAME เกมสล็อตก็พร้อมที่จะแตก <a href="https://movie999.net/">ดูหนังออนไลน์ฟรี</a> ให้กับท่านแน่นอน เพราะเป็นระบบการสุ่มทั้งหมด เว็บตรง 1 บาทก็ ถอนได้ ไม่มีการโกง ปลอดภัยแน่นอน

Reply

<a href="https://betflix-pg.com/blogs/betflix-%E0%B9%80%E0%B8%84%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%94%E0%B8%B4%E0%B8%95%E0%B8%9F%E0%B8%A3%E0%B8%B5-100/">BETFLIX เครดิตฟรี 100</a> เว็บไซต์ดี เกมมาใหม่ มาแรงเยอะต้อง BETFLIX เครดิตฟรี 100 เว็บเกมดีอันดับ 1 มาแรงมาก เพราะเว็บของเรานั้น มีคุณภาพ มั่นคง ปลอดภัย เข้าสู่ระบบสล็อต ในรูปแบบอัตโนมัติที่ สล็อตเว็บตรงแตกดี เพื่ออำนวยความ สะดวกให้กับ ผู้เข้ามาใช้บริการ ผ่านทางเว็บ ผู้ให้บริการเกมสล็อต<a href="https://vitreriechatillon.net/straight-web-slots-are-good/">สล็อตเว็บตรงแตกดี</a> เพื่อความสะดวก รวดเร็ว ระบบที่ทันสมัย มีประสิทธิภาพสูงสุด เข้าสู่ระบบสล็อต เว็บสล็อตแตกง่าย ที่ได้รับความ นิยมอย่างรวดเร็ว หากท่านกำลังมองหาเว็บตรง <a href="https://movie999.net/">หนังใหม่</a> สล็อตเว็บใหญ่ที่สุด เราขอแนะนำ เว็บสล็อตแตกง่าย เว็บสล็อตแตกง่าย 2022 ล่าสุด

Reply

สวัสดี นักเล่นสล็อตทุกท่าน วันนี้ MEGA GAME มีเกม สนุกๆ มารีวิว ให้ทุกท่านกันอีกเช่นเคย เกมที่ทางเราจะนำมารีวิววันนี้ก็คือ เกมสล็อต PG Oriental Prosperity SLOT เกม พีจี มาใหม่ 2022 สล็อต <a href="https://www.megagame168.co/mega-game-oriental-prosperity/"> MEGA GAME </a> ความรัก ของ คู่ หนุ่มสาว ที่มีสัญญาต่อกัน อย่างสุดซึ้ง แต่ด้วยความแตกต่าง กันทางฐานะ และ ชนชั้น ดูหนังฟรี<a href="https://movie999.net/"> ดูหนังฟรี</a>

Reply

ในตอนนี้ใคร ๆ ก็อยากมีรายได้ที่ดี และ เล่นได้ง่ายๆ โดยไม่ต้องฝาก ก็สามารถหารายได้ง่าย ๆ และ <a href="https://mega-game.io/mega-game-%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%b4%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%9f%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b5%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b1%e0%b8%9a%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%8730/"> สล็อต</a> ได้รับความชื่นชอบ เป็นอย่างมากสล็อตMEGA GAME เราได้เปิดให้ผู้เล่นได้ใช้งาน อย่างสนุกสนาน หากเพื่อน ๆ<a href="https://betflixauto89.com/"> BETFLIX</a> คนไหนที่สนใจ อยากจะเล่นเกมของเรา สามารถนำเครดิตฟรีของ เราได้เลยทันที เครดิตฟรีกดรับเอง30 ทางเราไม่ได้มีแค่ เกมสล็อตเพียงอย่างเดียว มีทั้งบาคาร่าอีกด้วย <a href="https://movie999.net/">ดูหนังออนไลน์ฟรี</a>เพื่อให้ผู้เล่นได้เล่นอย่าง สนุกสนาน มีให้เลือกเล่นมากว่า 3000 เกม มีแต่เกมที่สนุก ๆ<a href="https://mega-game.io/mega-game-%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%b4%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%9f%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b5%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%94%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%b1%e0%b8%9a%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%8730/"> เครดิตฟรีกดรับเอง30</a>

Reply

Free to play, leading, premium, surf strategy, strategy, strategy, strategy, engine... Multi surf for free Go and try to play until you may think that surfing the web. and recommend that you do not stray from the slot game that has it all <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/pgslot" > pgslot </a> , <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/"> ambbet </a>

Reply

ไม่ว่าผู้เล่น สล็อต จะอยู่ที่ไหนก็เล่นได้ ตลอดเวลาทางเราเปิดให้ ผู้เล่นได้เล่นตลอด 24 ชั่วโมง <a href="https://www.megagame168.co/mega-game-pg-slot-%e0%b8%97%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%87%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%82%e0%b9%89%e0%b8%b2/"> สล็อต</a>กันเลยทีเดียว เล่นเกมของเราได้ ทุกเกมสามารถดู ได้ที่หน้าเว็บ MEGA GAME เล่นง่ายๆ และ ทางเรายังมีให้ผู้เล่นได้<a href="https://movie999.net/">ดูหนังออนไลน์ฟรี</a> ดูหนังออนไลน์ อีกด้วยง่าย ๆเพียงแค่มี มือถือ ก็สามารถเข้า มาเล่นที่ pg slot ทางเข้า ของเราได้เลยเล่น ได้ไม่มีขีดอย่างแน่นอน รองรับ

Reply

เพื่อความสะดวกสบาย ในการเดิมพัน <a href="https://www.megagame168.co/เมก้า-เกม-สล็อต/">MEGA GAME</a> สร้างกำไรจากการเล่นเกมสล็อตออนไลน์ เราได้จัดเตรียม สล็อต MEGA GAME ทุกค่าย ที่เข้าถึงได้ง่ายสุดๆ ไม่มีความยุ่งยาก จะเข้าเล่นเกมสล็อต megagame-auto จะเข้าเล่นเกมสล็อตฟรี ก็สะดวกสบายด้วยระบบการเข้าถึงที่สมัยที่สุด อำนวยความสะดวกมากยิ่งขึ้นด้วยระบบการทำธุรกรรมแบบกำหนดเองอย่างรวดเร็วโดยอัตโนมัติ <a href="https://movie999.net/">หนังใหม่</a> สามารถที่จะเข้าเกมผ่านทางเข้า เมก้า เกม สล็อต บนเว็บไซต์ของเรา ในเบราว์เซอร์ของคุณ

Reply

Free credit without deposit By putting this type of measure will be a free credit like you. no deposit required But you have to join the activities on the web. You get these free credits. used to play or actually used to play There is a chance to actually withdraw it. which you have to play to have a turnover or the total amount of the game to reach the specified You will be able to withdraw. To prevent people who come to claim free credit without depositing money. <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/?_bcid=629b230f1efbec22cbc94dff&_btmp=1654334223">ambbet</a>

Reply

on this web

Reply

on this web

Reply

Buffalo Win

Reply

Buffalo Win

Reply

especially free credit that you do not need to deposit We have a variety of ways for you to choose from. It depends on you that you are good at getting free credits in any form, such as free credits in mini games. It's a free credit that you get when you go into the game and break the score. of mini-games on the web page which if you can make your score statistics higher than the specified score You will receive free credit immediately. or every time you can break the same record You will also receive free credits, which here will be free credits. that you can do every day <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/pgslot?_bcid=62add6f425c46b7d6c73cb08&_btmp=1655559924">pgslot</a>

Reply

6/19/2022 04:27:32 am

BETFLIX เครดิตฟรี 50 ล่าสุด 2022 รับได้ง่ายๆ ในไม่กี่ขั้นตอน หรือผ่านทางกิจกรรมต่างๆ หากผู้เล่นทุกท่านสมัครสมาชิก กับ เว็บสล็อตออนไลน์ของ BETFLIXAUTO89 เพียงเท่านี้ ผู้เล่นทุกท่านก็สามารถรับ เครดิตฟรี ที่มีจำนวนจำกัดได้ทันที

Reply

There are also many interesting slot games. You can follow the article of joker123, you will not miss any news. Useful in playing slots and will make you real money because there are many articles from how to play until the slot games that make you money And there are also ways to receive various bonus promotions. For you to read much more, don't wait. Play online slots with joker 123. Easy to apply. Sign up for free. Get a bonus right away. <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/?_bcid=62b2db37f2d82cfcc3961e65&_btmp=1655888695">ambbet</a>

Reply

People may lose their human relationship with those around them because their focus is on the screen for too long, so we may not talk to anyone at all until it spoils the human relationship with those around us because of the result that we Play the game and focus on playing until you don't care about the people around you.

Reply

Online slots, the reason for making money, people in this era

Reply

Online slots, the reason for making money, people in this era

Reply

AMB Slot, a new type of slot game camp. with slot games for you to choose from, almost every game camp and in addition to slot games gathered in all game camps There are also other types of betting games. Whether it's baccarat, sic bo or fish shooting games, it's available for you to choose from. <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/pgslot?_bcid=62b998a873000a72d00273e7&_btmp=1656330408">pgslot</a>

Reply

joker123 Our website has gained a lot of popularity due to the fact that people come to play many different games and another game that is equally popular is the fish shooting game that has been very popular. <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/pgslot?_bcid=62bba98073000a72d002ae6b&_btmp=1656465792">pgslot</a>

Reply

Many people are still addicted to playing. in old style That is, if you want money from playing here a lot or starting that should not be less over a thousand per day will be considered the least and don't waste time to come in here Should be able to play at least 2 hours a day, or some people may force themselves to continue playing at 2 hours and per day should not have to play more than 3 rounds of games <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/?_bcid=62bd5c196cd50d28937a9c1d&_btmp=1656577049">ambbet</a>

Reply

This camp is another betting game that you should not miss because it is the most popular right now, especially the most popular games in this camp are online slot games, but not only online slot games, there are many other games for us to choose from, and the chance to make money is not difficult, just because you are studying how to play the basics, it will allow you to learn the different parts. <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/pgslot?_bcid=62bd5d946cd50d28937a9c83&_btmp=1656577428">pgslot</a>

Reply

This camp is another betting game that you should not miss because it is the most popular right now, especially the most popular games in this camp are online slot games, but not only online slot games, there are many other games for us to choose from, and the chance to make money is not difficult, just because you are studying how to play the basics, it will allow you to learn the different parts. <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/pgslot?_bcid=62bd5d946cd50d28937a9c83&_btmp=1656577428">pgslot</a>

Reply

It takes less than 2 minutes to apply for membership, 3 steps only. If you want to get rich first, you need to hurry up to apply. Don't wait because if you apply first, you can make money first and get rich easily. When you want to become a member with some of us, let's take a look at the application process. <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/pgslot?_bcid=62bef5884b3976046363f2cb&_btmp=1656681864">pgslot</a>

Reply

1. Online slots games that make money for players to be number 1 is Asgard. It is a popular game of the superslot camp that has it all because it is a game that makes me profit. And bonus rewards are issued most often. Makes many players choose to play this game as the top one ever. The game is interesting and fun to play because it is built from the plot. the god of thunder This game doesn't cost a lot of money. good profit To play slots Recommend this game the most fun to play. <a href=" https://haichok56.com/?_bcid=62bfa6fd4b3976046364418c&_btmp=1656727294">บาคาร่า</a>

Reply

including the rate to adjust the payout that is higher than before All this will tell us with certainty that The time to come in to play doesn't have to be very long, up to hours to have a lot of money out of the game. <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/pgslot?_bcid=62bfbcc54ff92a926e6bbccd&_btmp=1656732870">pgslot</a>

Reply

So today if you want to try to become an amateur Casino games we have An interesting game and it's going strong. At present, to introduce you Have tried to apply for membership and start playing this online casino game with us. It is believed that it will give players more fun, excitement, and more income from playing these online casino games.

Reply

Along with playing exclusive online games that are superior in a format that can't be played anywhere else With a service that is straightforward and full of variety of online games. new and unique with both cute game themes An online game in an intense adventure genre. <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/pgslot?_bcid=62c00d2e4b3976046364840a&_btmp=1656753454">pgslot</a>

Reply

Slots are the most popular online games. The game with the fastest mobile phone support for smartphones. and the most convenient because with the method of applying through the automatic system And there is a fast deposit with an automatic system. Importantly, there is no limited area to play using the Internet to connect to this. Making money with online games is very easy in this era. Fish shooting games. If talking about this game, no one would know for sure. <a href="https://haichok56.com/?_bcid=62c05b964ff92a926e6bf1c6&_btmp=1656773526">บาคาร่า</a>

Reply

pg123game, a famous website, easy to make money, the best PG slot website, 2022 is ready to take you to catch hundreds of thousands of money. From the simple beginning, full of good quality slots games, fast jackpots, selected for you to choose to play and make more than 200 games, guaranteed fun. Unlimited fun We give you freedom from unlimited bets. Is a web slot with little capital, no minimum, that hosts a big promotion, unlimited service, guarantees that the system is good, the system is fast, continuously updated Ready to update the game, easy to play, easy to break, the latest PG camp, go together <a href="https://www.itsallgame.com?_bcid=62c1d6e54b39760463657cb6&_btmp=1656870629">superSlot</a> <a href="https://www.itsallgame.com/?_bcid=62c1f6994ff92a926e6c2161&_btmp=1656878745">pgslot</a> <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/?_bcid=62c1f6e04b39760463658a3c&_btmp=1656878816">สล็อต</a> <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/?_bcid=62c1f7474b39760463658a90&_btmp=1656878919">สล็อต</a>

Reply

pg123game, a famous website, easy to make money, the best PG slot website, 2022 is ready to take you to catch hundreds of thousands of money. From the simple beginning, full of good quality slots games, fast jackpots, selected for you to choose to play and make more than 200 games, guaranteed fun. Unlimited fun We give you freedom from unlimited bets. Is a web slot with little capital, no minimum, that hosts a big promotion, unlimited service, guarantees that the system is good, the system is fast, continuously updated Ready to update the game, easy to play, easy to break, the latest PG camp, go together <a href="https://www.winbigslot.com/?_bcid=62c1f7474b39760463658a90&_btmp=1656878919">สล็อต</a>

Reply

เล่นสล้อตออนไลน์กับเรา เว็บที่แจกรางวัลเยอะที่สุด พร้อมดปรโมชั่นสมาชิกใหม่ รับโบนัสฟรีทันที 50% แบบไม่ต้องรอช้า เว็บสล็อตดีๆ โปรดีดี ทางนี้เลย สำหรับสมาชิกใหม่ สมัครใหม่ รับฟรีเครดิตทันที สมัครง่าย โดยผ่านระบบ auto ในการสมัคร และฝากถอนเงิน คลิ๊กสมัคร https://www.megaslot.to

Reply

Along with playing exclusive online games that are superior in a format that can't be played anywhere else With a service that is straightforward and full of variety of online games. new and unique with both cute game themes An online game in an intense adventure genre. <a href="https://www.ambgiant.com/pgslot?_bcid=62c00d2e4b3976046364840a&_btmp=1656753454">pgslot</a>

Reply

8/4/2022 07:11:08 am

Thеse аre truⅼy enormous ideas іn cօncerning blogging. Уoս have touhed somе nice thіngs һere. Any way keep սp wrinting.

Reply

8/4/2022 07:11:53 am

Thеse аre truⅼy enormous ideas іn cօncerning blogging. Уoս have touhed somе nice thіngs һere. Any way keep սp wrinting.

Reply

8/11/2022 03:11:48 am

หนังใหม่ชนโรง หนัง 18+ ดูหนังฟรีออนไลน์ เต็มเรื่อง hd 4k เว็บดูหนังชนโรงใหม่ 2022 เต็มเรื่องพากย์ไทยชนโรง หนังใหม่ล่าสุด movie-1.com ดูหนังออนไลน์ hd ฟรี ซีรี่ย์ หนังออนไลน์มันๆ หนังจีน เต็มเรื่อง ดูหนังออนไลน์ฟรี 2022 แนะนำหนังน่าดูเอเชียและฮอลลีวูด เว็บดูหนังออนไลน์ฟรี 24 ชั่วโมง มาสเตอร์ชัด 4k ทั้งภาพและเสียง ดูบนมือถือ โหลดไวไม่มีกระตุก

Reply

Most importantly, however, the Supreme Court’s decision on sports betting means that you will now be able to lose your money legally – which, either right away or over time, you are exceedingly likely to do. <a href="https://www.ufa60s.com/tag/ฟรีบาคาร่า/" >ufa60s.com/tag/ฟรีบาคาร่า/</a>

Reply

8/24/2022 06:59:46 am

Private hospitals were also allowed to do COVID tests however, they have not included their labs’ balance sheets in their turnovers, making it increasingly challenging to look through their invoices.

Reply

8/24/2022 07:00:44 am

The domain was repurposed to form a Bitcoin exchange and shortly afterwards a man by the name of Mark Karpeles bought the site. A few months after running on June 2011 the Bitcoin exchange faced with it’s first major hack which cost them at least 25,000 or an equivalent $8 million at the time.

Reply

9/8/2022 03:39:44 am

Thanks so much for providing individuals with remarkably marvellous opportunity to read articles and blog posts from this blog.

Reply

10/11/2022 12:41:40 am

<a href="https://pgslot78.vegas/">pg slot auto</a> เริ่มก่อน รวยก่อน เล่นเกมสล็อตได้เงินจริง

Reply

Great post <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">안전놀이터</a>! I am actually getting <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">안전공원</a>ready to across this information <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">검증사이트</a>, is very helpful my friend <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">온라인슬롯</a>. Also great blog here <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">온라인카지노</a> with all of the valuable information you have <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">바카라사이트</a>. up the good work <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">온라인바카라</a> you are doing here <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">토토사이트</a>. <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com"></a>

Reply

Great post <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">안전놀이터</a>! I am actually getting <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">안전공원</a>ready to across this information <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">검증사이트</a>, is very helpful my friend <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">온라인슬롯</a>. Also great blog here <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">온라인카지노</a> with all of the valuable information you have <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">바카라사이트</a>. Keep up the good work <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">온라인바카라</a> you are doing here <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com">토토사이트</a>. <a target="_blank" href="https://www.doracasinoslot.com"></a>

Reply

11/15/2022 07:40:21 am

Thanks with your Perception for your personal fantastic distributing. I’m exhilarated I've taken the time to find out this. It truly is under no circumstances sufficient; I will consider your World wide web web-site every day.<a href="https://in1.bet/" rel="nofollow">ทางเข้าสล็อต</a>

Reply

11/16/2022 12:55:40 pm

I have review your publish-up couple of circumstances mainly because of the truth your views are by myself Normally. It is superb information and facts For each and every reader. <a href="https://in1.bet/" rel="nofollow">ทางเข้าสล็อต</a>

Reply

เกมสล็อต ค่าย pg เว็บตรง

11/22/2022 11:37:36 pm

<a href="https://pg-slot.game/%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%a7%e0%b8%a1%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%97%e0%b8%84%e0%b8%a7%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%a1/%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%81%e0%b8%a1%e0%b8%aa%e0%b8%a5%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%ad%e0%b8%95-%e0%b8%84%e0%b9%88%e0%b8%b2%e0%b8%a2-pg-%e0%b9%80%e0%b8%a7%e0%b9%87%e0%b8%9a%e0%b8%95%e0%b8%a3%e0%b8%87/">เกมสล็อต ค่าย pg เว็บตรง</a>เกมสล็อตค่าย PGSLOT ออกใหม่ พร้อมให้ผู้เล่นทุกคนได้รับโบนัสทดลองเล่นสล็อต pg ฟรี 2022 แล้ววันนี้ ที่นี้ที่เดียว PGSLOT GAME ได้เล่นก่อนใครเพื่อน

Reply

11/24/2022 05:11:59 am

Fantastic submitting. Fascinating to look at. I like to examine these an amazing publish-up. Many thanks! It truly is manufactured my endeavor far more and additional easy. Keep on to help keep rocking. <a href=https://iznine.com/rel="nofollow">บาคาร่าออนไลน์</a>

Reply

12/5/2022 05:24:22 am

Efficiently released info. It will probably be thriving to anybody who helps make usage of it, counting me. Keep up The great conduct. For selected I will evaluation out further posts Operating working day in and day out. <a href=https://iznine.com/rel="nofollow">บาคาร่าออนไลน์</a>

Reply

12/7/2022 12:38:36 am

<a href="https://in1.bet/" rel="nofollow">แทงบอลออนไลน์</a> It so cool site

Reply

12/7/2022 10:11:43 am

I like checking out internet web-sites in my spare time. I have frequented A good number of web pages but did not run into any web page extra effective than yours. Thanks for that nudge!

Reply

12/22/2022 07:02:54 am

That appears to generally be wonderful Conversely I'm continue not to significantly much too certain which i like it. At any demand will appear way more into it and judge Individually! <a href=https://iznine.com/rel="nofollow">สล็อตวอเลท</a>

Reply

12/25/2022 08:33:37 am

Thank you a lot while you transpire to be prepared to share details with us. We'll for good admire all you might have completed detailed in this article since you have developed my do The task so simple as ABC. <a href=https://iznine.com/rel="nofollow">สล็อตเว็บตรง</a>

Reply

12/25/2022 09:47:22 am

I went to this Internet site, and I truly feel that you've got a a whole lot of excellent details, I've saved your internet site to my bookmarks. <a href="https://in1.bet/" rel="nofollow">สมัครslotpg</a>

Reply

1/4/2023 06:33:23 am

You've outdone oneself this time. It might be the easiest, most transient step by step details that I have Anytime witnessed. <a href=https://iznine.com/rel="nofollow">หวยออนไลน์</a>

Reply

1/4/2023 12:20:05 pm

This write-up is basically a fascinating prosperity of useful useful That could be exciting and really nicely-penned. I commend your exertions on this and thanks for this specifics. I understand it exceptionally correctly that if Absolutely everyone visits your web site site, then he/she will definitely revisit it over again. <a href="https://in1.bet/" rel="nofollow">สมัครslotpg</a>

Reply

1/6/2023 07:57:47 am

It is really a proficiently-investigated information and outstanding wording. I obtained so engaged On this substance which i couldn’t wait all around inspecting. I'm surprised together with your do The task and skill. Thanks. <a href=https://iznine.com/rel="nofollow">บาคาร่าออนไลน์</a>

Reply

1/6/2023 12:53:56 pm

Excellent report! I need persons to grasp just how excellent this facts is as section within your posting. Your sights are similar to my pretty own relating to this situation. I'll take a look at on a daily basis your website generally for the reason that I am knowledgeable. It could be pretty valuable for me. <a href="https://in1.bet/" rel="nofollow">สมัครslotpg</a>

Reply

1/15/2023 12:06:35 am

ขอบคุณที่ให้พื้นที่แชร์ข้อมมูลต่างๆสำหรับเรา <a href="https://pgslot78.vegas/">สล็อต แตกง่าย</a> โปรดเข้ามาแวะชมเว็บไซร์ของเรา

Reply

1/15/2023 12:09:23 am

ขอบคุณที่ให้พื้นที่สำหรับทำประโยชน์กับเรา <a href="https://pgslot-games.com/pg-slot-ทดลองเล่น/">ทดลอง เล่น สล็อต</a> แวะเข้ามาชมเว็บไซร์เราได้เสมอ

Reply

1/15/2023 12:11:24 am

ร่วมสนุกกันกับ เมก้า ของเรา <a href="https://megagame.vegas/slot-demo/">ทดลองเล่น mega</a> เข้ามาเล่นกันเยอะๆนะครับ

Reply

1/29/2023 08:27:54 am

<a href="https://pgslot78.vegas/">pg slot auto</a> เริ่มก่อน รวยก่อน เล่นเกมสล็อตได้เงินจริง

Reply

1/29/2023 08:28:27 am

<a href="https://pgslot-games.com/">pg slot ใหม่ล่าสุด</a> เล่นสล็อตฟรี ได้เงินจริงไหม ตอบทุกคำถามที่สงสัย

Reply

1/29/2023 08:28:45 am

<a href="https://megagame.vegas/">megagame.vegas</a> สล็อตออนไลน์ ร่วมต่อสู้และล่าสมบัติไปกับเรา

Reply

2/9/2023 05:18:38 pm

Thank you a lot while you transpire to be prepared to share details with us. We'll for good admire all you might have completed detailed in this article since you have developed my do The task so simple as ABC. <a href="www.iznine.co" rel="follow">แทงบอลออนไลน์</a>

Reply

2/12/2023 09:50:46 am

Your function is definitely appreciated round the clock together with the environment. It truly is unbelievably an in depth and beneficial blog site site. <a href="www.iznine.co" rel="follow">สมัครslotpg</a>

Reply

2/14/2023 06:10:01 pm

Your function is definitely appreciated round the clock together with the environment. It truly is unbelievably an in depth and beneficial blog site site. <a href="www.iznine.co" rel="follow">สล็อตแตกง่าย</a>

Reply

feer

2/16/2023 10:23:28 am

https://www.google.com/

Reply

3/13/2023 05:28:47 pm

ฉันเพิ่งเริ่มใช้แพลตฟอร์มการจัดการโซเชียลมีเดียสำหรับธุรกิจขนาดเล็กของฉัน และช่วยให้ฉันเข้าถึงผู้ชมได้กว้างขึ้น ช่วยให้ฉันกำหนดเวลาโพสต์ล่วงหน้าและให้ข้อมูลเชิงลึกอันมีค่าเกี่ยวกับพฤติกรรมของผู้ชมได้ ฉันขอแนะนำแพลตฟอร์มนี้ให้กับเจ้าของธุรกิจขนาดเล็ก

Reply

3/13/2023 06:04:29 pm

เมื่อเร็วๆ นี้ฉันมีปัญหากับการสั่งซื้อบนเว็บไซต์นี้ และทีมบริการลูกค้าของพวกเขาก็ให้ความช่วยเหลือในการแก้ไขปัญหา พวกเขาอดทนและเข้าใจ และทำให้แน่ใจว่าฉันพอใจกับผลลัพธ์ที่ได้ เห็นได้ชัดว่าพวกเขาให้ความสำคัญกับลูกค้าและมุ่งมั่นที่จะมอบประสบการณ์ที่ดี

Reply

3/14/2023 02:46:06 am

I love how you approached this topic in a non-biased way, it's refreshing to read something that's not pushing an agenda.

Reply

3/20/2023 04:39:44 am

Leather jackets with fur have become increasingly popular in recent years, combining the timeless style of a leather jacket with the added warmth and texture of fur. These jackets typically feature a leather exterior and a fur lining or collar, often made from materials like shearling or faux fur. The fur adds an extra layer of insulation, making the jacket ideal for colder temperatures. Leather jackets with fur can be found in a variety of styles, from classic biker jackets with a shearling collar to more modern designs with fur accents on the sleeves or body. Some jackets may also feature fur trims or panels for added texture and visual interest. These jackets have become a favorite among both men and women, appealing to those who want a stylish and practical piece of outerwear that can be worn in a variety of settings, from casual outings to formal occasions. A leather jacket with fur is a statement piece that adds a touch of luxury and sophistication to any outfit.

Reply

4/27/2023 12:49:22 am

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and

Reply

5/18/2023 05:30:00 am

Great Job! This very informative and resourceful article. Please keep on posting.

Reply

5/26/2023 07:08:10 am

Excellent! Thank you for this post. This is very helpful and resourceful article. Congrats and keep posting! You may visit also my website at

Reply

5/27/2023 06:15:33 am

this Top Gun Jacket now to increase your level of excitement

Reply

6/13/2023 03:25:12 pm

ทางเข้าbiogaming เทคนิค บาคาร่า ใช้ได้จริง รู้ไว้ทำกำไรชัวร์

Reply

hey, honestly become privy to your weblog through google, and located that it’s honestly informative. I am going to observe out for brussels. I’ll respect if you proceed this in destiny. A variety of other oldsters may be benefited out of your writing. Hello there! Might you mind if i percentage your weblog with my twitter organization? There’s quite a few humans that i assume would certainly recognize your content. Please allow me realize. Many thanks i¦ve study numerous simply right stuff right here. Honestly rate bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot attempt you place to make such a super informative net web page.

Reply

6/14/2023 01:20:18 am

i and also my pals ended up following the best thoughts from the blog and so fast i got a horrible feeling i in no way expressed respect to the internet web page proprietor for the ones strategies. The girls have been surely warmed to study thru them and also have quite lots been making the most of them. Recognize your becoming well thoughtful and additionally for deciding on certain critical issues the majority are in reality desiring to be aware about. Our personal sincere remorse for not expressing appreciation to earlier. Had to compose you that very little remark so as to mention thanks lots once more approximately the beautiful methods you've got proven in this situation. It turned into so enormously generous with you to provide unhampered exactly what a few humans might’ve bought as an electronic ebook to earn a few income on their personal, precisely for the reason that you can likely have performed it if you desired. Those techniques as nicely served like the exquisite manner to understand that the relaxation have the identical zeal sincerely like mine to understand loads more bearing on this trouble. I am sure there are lots of more fun classes up front for individuals that scan your weblog post.

Reply

hello, i do think that is a super net website online. I stumbledupon it i’m going to return all over again considering i've bookmarked it. Money and freedom is the best manner to exchange, may additionally you be rich and preserve to assist other human beings. You are so interesting! I don’t agree with i've read thru anything like this earlier than. So quality to find out any person with some specific mind in this topic. Critically.. Many thank you for starting this up. This web site is one issue that’s needed at the net, someone with a few originality! I’m impressed, i must say. Seldom do i come upon a blog thats both educative and enjoyable, and allow me inform you, you have got hit the nail on the pinnacle. The problem is something which now not sufficient folks are speaking intelligently about. I'm very glad that i stumbled throughout this all through my search for something concerning this.

Reply

my accomplice and that i in realitbsite online, how can i subscribe for a weblog web website? The account aided me a applicable deal. I had been a bit bit familiar of this your broadcast supplied vivid clean idea <a href="https://archmule.com/s/tasks/c9a7ba12-d5d0-4159-9b37-b47f1209ce29/meogtipolice">먹튀검증하는곳</a>

Reply

6/14/2023 02:24:45 am

i exactly wanted to understand yte job your are putting in instructing different people thru your weblog. Greater than probably you've got by no means got to recognise any folks. I’m writing to will let you be aware about what a beneficial discovery my cousin’s princess gained surfing your webblog. She got here to discover too many things, such as what it's miles like to own an high-quality education heart to get the others effortlessly know simply exactly several impossible topics. You clearly passed her goals. Many thanks for giving such valuable, trusted, explanatory and in addition fun suggestions on the subject to sandra. <a href="https://degentevakana.com/blogs/view/70060">ok토토 먹튀검증사이트</a>

Reply

6/14/2023 02:41:43 am

i am very happy to study this. This is the sort of guide that needs to take delivery of and not the random incorrect information this is at the other blogs. Respect your sharing this greatest doc. Thank you a gaggle for sharing this with anyone you truely understand what you’re speaking approximately! Bookmarked. Kindly additionally communicate over with my website =). We will have a link change arrangement amongst us! Thank you for any other superb publish. Wherein else may also anyone get that type of information in this sort of best method of writing? I’ve a presentation next week, and i am at the look for such records. <a href="https://totowidget.thinkific.com/courses/totowidget">토토위젯검증커뮤니티</a>

Reply

hiya ! I'm a pupil writing a record on the subject of your publish. Your article is a piece of writing with all of the content material and topics. I have ever desired . Thanks to this, it will likely be of amazing help to the file i'm preparing now. Thank you in your difficult work. And if you have time, please visit my web page as properly. is one very exciting post. Like the way you write and i will bookmark your blog to my favorites. Strong weblog. I acquired numerous fine data. I? Ve been keeping a watch fixed in this technology for a while. <a href="https://warriorsofradness.webflow.io/">토토서치 먹튀검색</a>

Reply

studying your weblog is manner better than snuggles. It is very informative and that i bet you are very informed on this vicinity. I lived out in alaska so i recognize what you are speaking approximately here. My girlfriend introduced me in your posts. Must say, i definitely like what you have executed to your website. Your factors pang.tribeplatform.com/general/post/onrain-seulrose-daehan-gunggeugjeogin-gaideu-TvtPOJoXrex86OM">토토팡검증사이트</a>

Reply

i enjoy you due to all of your precious work on this net web page. My niece delights in doing investigations and it is simple to understand why. Each person hear all concerning the effective approaches you produce fine tricks by means of your web weblog and consequently cause contribution from different people at the problem so our baby is honestly being taught a lot. Enjoy the rest of the brand new year. You have got been appearing a pretty cool task. I need to bring my affection on your kindness giving help to ladies and men who actually need steerage on on this area of interest. Your non-public determination to passing the solution all around has been truely high-quality and feature continuously allowed those like me to get to their objectives. Your tremendous beneficial pointers and tips denotes an entire lot to me and additionally to my colleagues. Thank you a ton; from everyone. Thank you for all of the difficult work in this web website online. Ellie delights in coping with investigations and it’s easy to peer why. A number of people pay attention all about the energetic approach you produce superb guidelines at the web site and in addition to purpose reaction from the others in this issue and my princess is coming across a lot. Take advantage of the relaxation of the new yr. You’re doing a tremendous activity.

Reply

6/14/2023 04:13:07 am

hello! I’m at paintings surfing round your weblog from my new apple iphone! Just wanted to mention i like analyzing thru your blog and sit up for all of your posts! Preserve up the outstanding work! Simply desired to increase a brief observe in an effort to thanks for all the super processes you're writing right here. My long internet research has now been rewarded with good insight to speak approximately with my pals and classmates. I ‘d say that most of us visitors are extremely blessed to dwell in a magnificent vicinity with many unique individuals with beneficial pointers. I sense pretty lucky to have used your internet web page and look ahead to lots of greater a laugh instances reading right here. Thanks over again for lots of things. Woah! I’m without a doubt loving the template/topic of this weblog. It’s simple, but powerful. A lot of instances it’s very tough to get that “perfect stability” among excellent usability and look. I must say you have got carried out a great job with this. Additionally, the blog masses extraordinarily fast for me on chrome. Outstanding blog!

Reply

6/14/2023 05:07:54 am

i should explicit way to this creator just for bailing me out of this precise problem. Simply after browsing via the engines like google and obtaining fundamentals that had been not quality, i thought my complete lifestyles become gone. Being alive minus the solutions to the issues you've got fixed via way of your true quick put up is a important case, in addition to the type that might have in a poor way affected my whole profession if i had not encounter your internet blog. Your main functionality and kindness in touching each part become essential. I'm now not certain what i might have achieved if i had no longer encountered one of these stuff like this. I also can at the moment sit up for my destiny. Thank you a lot a lot for the reliable and exquisite manual. I will now not assume twice to suggest your web web site to everybody who needs to have assistance on this situation remember. I’m additionally writing to let you be aware of of the beneficial come upon my princess discovered studying your web page. She came to discover too many problems, maximum substantially what it's miles like to have an fantastic assisting nature to have other human beings completely recognize a number of superior matters. You definitely surpassed site visitors’ expectations. Thanks for generating the ones excellent, safe, instructional and similarly cool thoughts on the topic to janet.

Reply

6/14/2023 06:02:04 am

"this is exceptional weblog! So much to analyze! Keep posting and sharing! But hello, in case your looking for notable site. similarly, various related websites are registered inside the menu. The more you come, the greater information you could offer. It's far in reality a nice and beneficial piece of facts. I'm glad which you simply shared this helpful data with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing .

Reply

the next time i examine a blog, i'm hoping that it doesnt disappoint me as tons as this one. I suggest, i understand it became my desire to study, however i really thought youd have some thing thrilling to say. All i listen is a group of whining approximately some thing that you may restoration if you werent too busy searching out attention. Hello, i think your site is probably having browser compatibility troubles. Once i study your internet site in safari, it appears pleasant but when starting in net explorer, it has some overlapping. I just wanted to present you a short heads up! Different then that, exceptional weblog!

Reply

"your web site is very fine, and it is very helping us this publish is unique and interesting, thanks for sharing this fantastic information. And go to our blog web site additionally. Incredible article! That is the sort of data which are meant to

Reply

Thanks for writing such amazing content. Your ideas help me every time I read it to work easily and calmly. I like to spend my free time reading your Blogs and learning new things from it. I want to appreciate your work. Good Job. Your writing includes a creative idea that is useful for me as a reader. Your information is amazing and original and attracts readers who love reading such articles like that. You can impress a person with your writing skills. We want to read your more blogs with some more creativity. Your content that you have posted here is fantastic that will not confuse the person but surely impress and attract the readers. <a href="https://aguilarojalapelicula12.weebly.com/">먹폴</a>

Reply

6/20/2023 01:40:40 am

For a long time me & my friend were searching for informative blogs, but now I am on the right place guys, you have made a room in my heart! It is extraordinary to have the chance to peruse a decent quality article with valuable data on subjects that bounty are intrigued one.I agree with your decisions and will enthusiastically anticipate your future updates. It is a completely interesting blog publish.I often visit your posts for my project's help about Diwali Bumper Lottery and your super writing capabilities genuinely go away me taken aback.Thank you a lot for this publish.

Reply

Wohh just what I was looking for, thanks for posting. Positive site, where did u come up with the information on this posting?I have read a few of the articles on your website now, and I really like your style. Thanks a million and please keep up the effective work. Surprising article. Hypnotizing to analyze. I genuinely love to analyze such a good article. Much regarded! keep shaking. I was truly thankful for the useful info on this fantastic subject along with similarly prepare for much more terrific messages. Many thanks a lot for valuing this refinement write-up with me. I am valuing it significantly! Preparing for an additional excellent article <a href="http://web-lance.net/blogs/post1705">토토</a>

Reply

6/20/2023 01:59:35 am

Superior post, keep up with this exceptional work✅. It's nice to know that this topic is being also covered on this web site so cheers for taking the time to discuss this! Thanks again and again! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a gathering of volunteers and new exercises in a comparative claim to fame. Blog gave us significant information to work. You have finished an amazing movement This post is extremely radiant. I extremely like this post. It is outstanding amongst other posts that I ve read in quite a while. Much obliged for this better than average post.

Reply

6/20/2023 02:04:31 am

Awesome dispatch! I am indeed getting apt to over this info, is truly neighborly my buddy. Likewise fantastic blog here among many of the costly info you acquire. Reserve up the beneficial process you are doing here. Thankful to you for your post, I look for such article along time, today I find it finally. this post give me piles of instigate it is to a marvelous degree relentless for me. Your post is very helpful to get some effective tips to reduce weight properly. You have shared various nice photos of the same. I would like to thank you for sharing these tips. Surely I will try this at home. Keep updating more simple tips like this.

Reply

6/20/2023 02:06:08 am

Hi, i think that i saw you visited my site so i came to “return the favor”.I am attempting to find things to enhance my website!I suppose its ok to use a few of your ideas!! I’m really glad I’ve found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish only about gossips and internet and this is actually irritating. A good blog with exciting content, this is what I need. Thanks for keeping this web-site, I will be visiting it. Thanks a lot for giving everyone remarkably marvellous chance to check tips from here. It can be very pleasant and as well , stuffed with a great time for me and my office friends to visit the blog <a href="https://www.homify.co.kr/ideabooks/9038531/%EC%8A%AC%EB%A1%AF-%EC%9E%AD%ED%8C%9F%EC%9C%BC%EB%A1%9C-%EC%9E%AD%ED%8C%9F%EC%9D%84-%EC%8A%AC%EB%A1%AF%ED%95%98%EB%8A%94-%EB%B0%A9%EB%B2%95">토토디펜드 검증커뮤니티</a>

Reply

6/20/2023 02:07:14 am

i am for the first time here you for the efforts you have made in writing this article. I am hoping the same best work from you in the future as well. In fact your creative writing abilities has inspired me to start my own Blog Engine blog now. Really the blogging is spreading its wings rapidly. <a href="https://www.pinterest.co.kr/pin/963840757728772265/">먹튀연구실 검증업체</a>

Reply

6/20/2023 02:08:00 am

Thanks for the wonderful share. Your article has proved your hard work and experience you have got in this field. Brilliant .i love it reading. I’m sure I will at last make a move using your tips on those things I could never have been able to touch alone. You had been so innovative to let me be one of those to benefit from your useful information. Please know how much I am thankful. Really decent post. I just discovered your blog and wished to say that I have truly cherished surfing around your blog entries. Regardless I'll be subscribing for your nourish and I trust you compose afresh soon! <a href="https://www.weedclub.com/blogs/member7256/onrain-kajino-siseol">토토매거진 검증업체</a>

Reply

Thank you because you have been willing to share information with us. we will always appreciate all you have done here because I know you are very concerned with our . I like your post. It is good to see you verbalize from the heart and clarity on this important subject can be easily observed.. i read a lot of stuff and i found that the way of writing to clearifing that exactly want to say was very good so i am impressed and ilike to come again in future.. Very useful post. This is my first time i visit here. I found so many interesting stuff in your blog especially its discussion. Really its great article. Keep it up. <a href="https://telescope.ac/meogtwitest/ota7vkvekvzyd3qogw5sjt">먹튀검역소먹튀제보</a>

Reply

I really enjoy simply reading all of your weblogs. Simply wanted to inform you that you have people like me who appreciate your work. Definitely a great post. Hats off to you! The information that you have provided is very helpful. Nice to be visiting your blog again, it has been months for me. Well this article that i've been waited for so long. I need this article to complete my assignment in the college, and it has the same topic with your article. Thanks, great share . Thanks for picking out the time to discuss this, I feel great about it and love studying more on this topic. It is extremely helpful for me. Thanks for such a valuable help again . <a href="http://web-lance.net/blogs/post1709">토토시대 먹튀검증</a>

Reply

I was just browsing through the internet looking for some information and came across your blog. I am impressed by the information that you have on this blog. It shows how well you understand this subject. Bookmarked this page, will come back for more. Thanks for the blog loaded with so many information. Stopping by your blog helped me to get what I was looking for. This is such a great resource that you are providing and you give it away for free. I love seeing blog that understand the value of providing a quality resource for free . Pretty good post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to say that I have really enjoyed reading your blog posts. Any way I'll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you post again soon. Big thanks for the useful info. <a href="https://calis.delfi.lv/blogs/posts/171127/lietotajs/292847-casinositekr/">카지노</a>

Reply

7/26/2023 03:11:55 am

Thanks for sharing this with so much of detailed information, its much more to learn from your article. Keep sharing such good stuff. Feel the luxury, wear the attitude - our handcrafted leather jackets are here to redefine elegance and prestige <a href="https://www.jacketars.com/product/womens-pink-leather-jacket/">leather jacket womens</a>

Reply

8/12/2023 07:23:58 am

ufabet789 เข้าสู่ระบบ เว็บพนันบอลที่ดีที่สุด เดิมพันง่าย 24ชม. แนะนำเกมสล็อต เกมน่าเล่น ทำกำไรง่าย แจ็คพอตแตกกระจาย

Reply

Great post <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">안전놀이터</a>! I am actually getting <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">안전공원</a>ready to across this information <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">검증사이트</a>, is very helpful my friend <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">온라인슬롯</a>. Also great blog here <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">온라인카지노</a> with all of the valuable information you have <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">바카라사이트</a>. Keep up the good work <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">온라인바카라</a> you are doing here <a target="_blank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com">토토사이트</a>. <a target="_blIank" href="https://www.erzcasino.com"></a>

Reply

11/20/2023 03:14:38 am

Sports, right off the bat, Betting Champ, John Morrison, is an incredibly famous sports handicapper, and expert player. In his 28 years, in the betting scene, he is yet to have a terrible season. For that reason he has procured the name of Sports Betting Champ. The design of your blog and your writing style actually inspire me. Is this a free theme, or did you make the modifications yourself? Whatever the case, keep up the fantastic writing.

Reply

A to a great degree brilliant blog passage. We are really grateful for your blog passage. fight, law usage You will find an extensive measure of techniques in the wake of heading off to your post. I was absolutely examining for. An obligation of appreciation is all together for such post and please keep it up. Mind blowing work.

Reply

11/28/2023 07:13:48 am

Decent data, profitable and phenomenal outline, as offer well done with smart thoughts and ideas, bunches of extraordinary data and motivation, both of which I require, on account of offer such an accommodating data her

Reply

12/3/2023 06:23:54 am

It's strikingly a marvelous and satisfying piece of information. I am satisfied that you in a general sense enabled this strong data to us. On the off chance that it's not all that much burden stay us sway forward thusly. Thankful to you for sharing

Reply

That is the excellent mindset, nonetheless is just not help to make every sence whatsoever preaching about that mather. Virtually any method many thanks in addition to i had endeavor to promote your own article in to delicius nevertheless it is apparently a dilemma using your information sites can you please recheck the idea. thanks once more <a href="https://ajslaos.com/guarantee.php">먹튀검증</a>

Reply

12/5/2023 04:36:37 am

arger businesses can manage and host internal events like all-hands and sales summits or external events like user conferences and consumer events and Zoom's biggest focus has always been large enterprises.

Reply

12/6/2023 11:45:31 pm

Easily, the article is actually the best topic on this registry related issue. I fit in with your conclusions and will eagerly look forward to your next updates. Just saying thanks will not just be sufficient, for the fantasti c lucidity in your writing. I will instantly grab your rss feed to stay informed of any updates.

Reply

I recently came across your blog and have been reading along. I thought I would leave my first comment. I don't know what to say except that I have enjoyed reading. Nice blog, I will keep visiting this blog very often <a href="https://tvxhd.com/#/tv">스포츠무료중계</a>

Reply

1/22/2024 11:56:57 pm

betfliknew ความท้าทายของเกมไม่ได้มาพร้อมกับความปลอดภัยของการเล่น. เว็บไซต์นี้ปฏิบัติการด้วยระบบที่มีความปลอดภัยสูงสุด, และทีมงานที่มีความเชี่ยวชาญที่พร้อมเสมอสนุกไปกับคุณทุกขั้นตอนของการเล่น

Reply

aomnoi

2/2/2024 09:32:27 am

บาคาร่าเว็บตรง ไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์ ฝากถอน ไม่มี ขั้นต่ำ พร้อมให้บริการคุณตลอด 24 ชั่วโมง

Reply

2/6/2024 12:17:59 am

It’s a very useful article. Very useful for everyone Hope you all read these stories.

Reply

2/8/2024 08:00:26 pm

I've recently completed reading your blog entry. Your information was truly captivating! It deeply connected with me due to my own personal experience. The way you wrote is incredibly captivating and resonating, and I gained valuable insights from your viewpoint. I appreciate you sharing your thoughts!

Reply

mike

2/9/2024 01:06:53 am

Direct online baccarat website Deposit-withdraw automatic system 100%

Reply

tt05

2/9/2024 03:05:23 am

Online baccarat, direct website, not through an agent, providing baccarat games that are easy to play. <a href="https://baccarat88th.com">บาคาร่า</a>

Reply

FF

2/9/2024 09:34:00 pm

Direct online baccarat website Deposit-withdrawal system, 100% automatic, fast withdrawal, trustworthy.

Reply

p

2/9/2024 11:40:11 pm

Baccarat, direct website, not through agents, deposits and withdrawals, no minimum, ready to serve you 24 hours a day, fast withdrawals, trustworthy.<a href="https://baccarat88th.com">บาคาร่าเว็บตรง</a>

Reply

Oasis

2/10/2024 10:43:56 pm

Online baccarat, direct website, not through an agent, providing baccarat games that are easy to play. <a href="https://baccarat88th.com">บาคาร่า</a>

Reply

2/19/2024 05:52:50 pm

Your blog post was a treasure trove of insight and engagement! Your unique approach, such as incorporating humor, vivid descriptions, and metaphors, brought the topic to life in my mind's eye. I felt like I was accompanying you on a journey. I'll be sure to keep an eye out for future posts on your blog.

Reply

2/22/2024 12:09:16 am

Your blog is fantastic! It's so easy to follow and filled with valuable insights. for more <a href="https://www.ornavo.pk/products/ornavo-first-aid-kit">First Aid Box</a>

Reply

2/23/2024 01:28:41 am

I went to this website, and I believe that you have a plenty of excellent information, I have saved your site to my bookmarks.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:38:30 am

You truly have a gift for creating original content. I appreciate the way you articulate your ideas in this piece and the way you think. Your writing style really strikes me. I appreciate you adding to the beauty of my experience.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:40:13 am

You really are talented at creating original articles. I admire your thought process and the manner you wrote this essay to share your opinions. Your writing style truly impresses me. I appreciate you making my experience even more lovely.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:40:50 am

Writing original content is a true skill of yours. In this post, you articulate your opinions in a way that I find appealing. Your writing technique really impresses me. I'm grateful that you enhanced the beauty of my encounter.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:41:44 am

You really have a gift for creating original articles. I appreciate your thought process and the manner you presented your points of view in this essay. Your writing style really impresses me. I appreciate how you enhanced the beauty of my experience.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:42:36 am

You truly have a gift for creating original content. I appreciate the way you articulate your ideas in this piece and the way you think. Your writing style really strikes me. I appreciate you adding to the beauty of my experience.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:43:46 am

Writing original content is a true skill of yours. In this post, you articulate your opinions in a way that I find appealing. Your writing technique really impresses me. I'm grateful that you enhanced the beauty of my encounter.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:44:58 am

You really have a gift for creating original articles. I appreciate your thought process and the manner you presented your points of view in this essay. Your writing style really impresses me. I appreciate how you enhanced the beauty of my experience.

Reply

3/3/2024 06:46:03 am

You really are talented at creating original articles. I admire your thought process and the manner you wrote this essay to share your opinions. Your writing style truly impresses me. I appreciate you making my experience even more lovely.

Reply

3/15/2024 03:15:43 am

Your blog is a captivating journey through the realms of [topic], weaving together expertise and passion seamlessly.

Reply

First and foremost, your positivity is infectious! In a world where negativity often dominates, stumbling upon a blog like yours is like discovering a hidden gem. Your ability to find the silver lining in every situation is truly admirable and serves as a beacon of hope for your readers.

Reply